Tiempo de lectura aprox: 3 minutos, 40 segundos

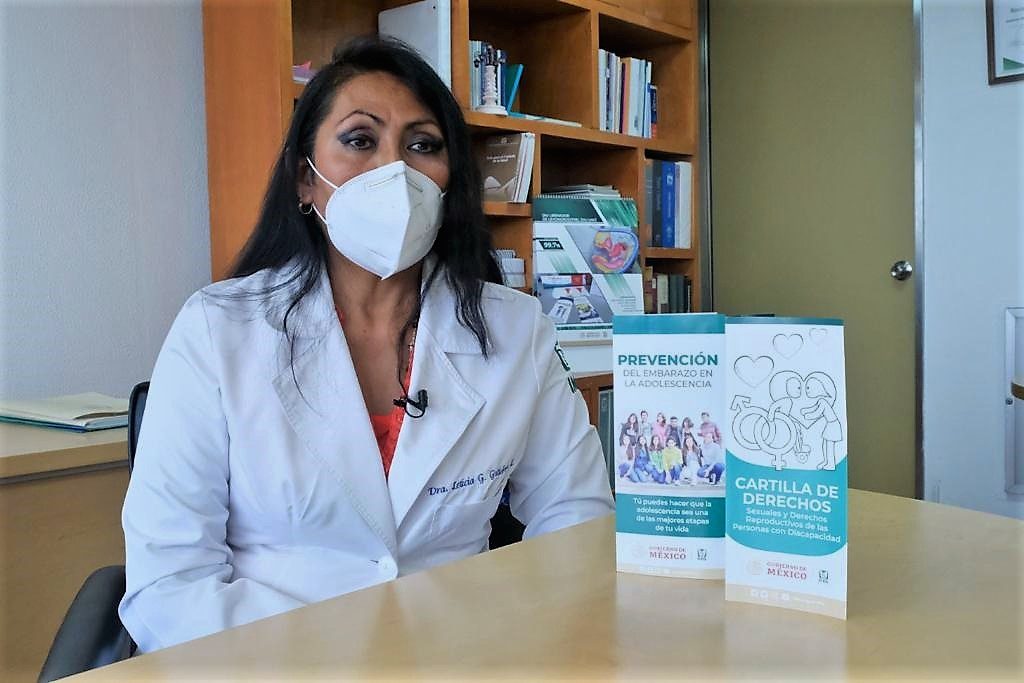

“La probabilidad de salvar una vida por la detección temprana es muy alta, es por eso la importancia de acudir a realizarse un papanicolaou, por lo menos una vez al año, para otorgar mayores posibilidades en las pacientes de detectar a tiempo enfermedades y dar tratamiento oportuno”, afirma la Dra. Priscilla Roque, especialista en Ginecología y Obstetricia del Hospital Sedna en el marco del Día Mundial de Cáncer Cervicouterino.

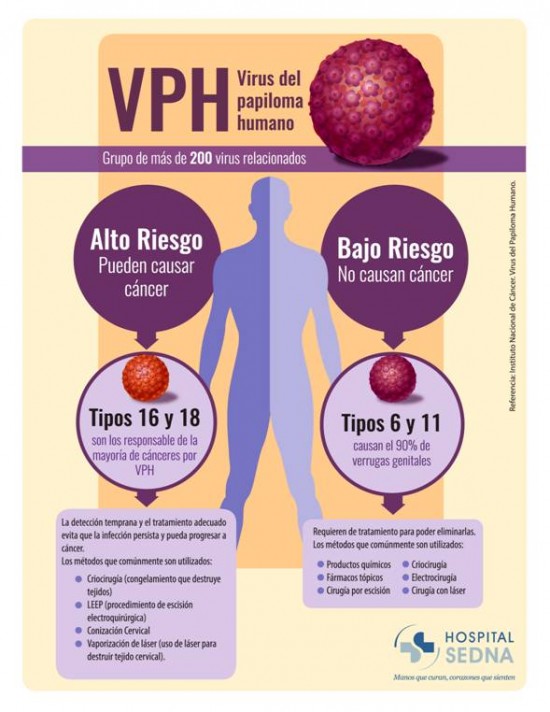

El cáncer cervicouterino es asociado a la infección por el virus de papiloma humano (VPH), el cual se transmite por contacto sexual y afecta a 8 de cada 10 personas (hombres y mujeres) en algún momento de la vida [3]. La mayoría de las infecciones por VPH ocurren sin síntomas, desaparecen en 1 o 2 años y no causan cáncer [4]. Sin embargo, algunas infecciones por VPH pueden persistir por muchos años y si no son tratadas, pueden evolucionar a cáncer.

En México desde el año 2006 el Cáncer Cervicouterino es la segunda causa de muerte en la mujer, tan solo en el 2014, se registraron 3,063 casos nuevos de tumores malignos de cuello uterino [6]. De acuerdo con la Dra. Priscilla Roque, asegura que “cualquier persona que sea sexualmente activa puede contraer VPH, ya sea por el contacto de piel con piel, sexo vaginal, anal u oral. Las infecciones por VPH son más probables en quienes tienen muchas parejas sexuales o tienen contacto sexual con alguien que tiene muchas parejas. Ya que la infección es tan común, la mayoría de la gente contrae infecciones por VPH poco tiempo después de hacerse activa sexualmente, así como la persona que ha tenido solo una pareja puede infectarse por VPH”.

“A cada variedad de virus en el grupo se le asigna un número, lo que es llamado tipo de VPH. La mayoría de los tipos de VPH causa verrugas en la piel, como en brazos, pecho, manos o pies. Otros tipos se encuentran principalmente sobre las membranas mucosas del cuerpo (capas superficiales húmedas que recubren los órganos y las partes del cuerpo que al abrirse quedan expuestas al exterior) como la cavidad vaginal y anal, así como la boca y la garganta”.

El uso correcto y regular del condón está relacionado con una transmisión menor de VPH entre las parejas sexuales, pero el uso irregular no lo está. Sin embargo, ya que las áreas que no están cubiertas por el condón pueden infectarse por el virus, estos no proveerán una protección completa contra la infección.

Las personas que no son activas sexualmente casi nunca presentan infecciones genitales por VPH. Además, la vacuna contra el VPH antes de la actividad sexual puede reducir el riesgo de infección. Estas vacunas proveen una fuerte protección contra las infecciones nuevas por VPH, pero no son eficaces para tratar infecciones por VPH ya existentes o enfermedades causadas por el mismo.

Sitios de interés

- Hospital Sedna http://www.hospitalsedna.com/es/

Referencias

- Instituto Nacional del Cáncer; Virus del Papiloma Humano y el Cáncer. Disponible en: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/causas-prevencion/riesgo/germenes-infecciosos/hoja-informativa-vph

- Instituto Nacional del Cáncer; Virus del Papiloma Humano y el Cáncer. Disponible en: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/causas-prevencion/riesgo/germenes-infecciosos/hoja-informativa-vph

- Secretaría de Salud; Cáncer de Cuello Uterino; Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/cancer-de-cuello-uterino

- Instituto Nacional del Cáncer; Virus del Papiloma Humano y el Cáncer. Disponible en: https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/causas-prevencion/riesgo/germenes-infecciosos/hoja-informativa-vph

- Secretaría de Salud; Cáncer de Cuello Uterino; Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/cancer-de-cuello-uterino

Bibliografía

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014Notificación de salida. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014. Accessed February 25, 2014.

- Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Reducing HPV-associated cancer globally. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia)2012;5(1):18-23.[PubMed Abstract]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 2004-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2012; 61(15):258-261.[PubMed Abstract]

- Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: Prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2013; 40(3):187-193.[PubMed Abstract]

- Chesson HW, Dunne EF, Hariri S, Markowitz LE. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 2014; 41(11):660-664.[PubMed Abstract]

- Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011; 204(4):566–573.[PubMed Abstract]

- Division of STD Prevention (1999). Prevention of genital HPV infection and sequelae: report of an external consultants’ meeting. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. New England Journal of Medicine 2006; 354(25):2645–2654.[PubMed Abstract]

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011; 29(32):4294–4301.[PubMed Abstract]

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowy DR. HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. Cancer 2008; 113(10 Suppl):3036-3046.[PubMed Abstract]

- de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: A review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncology 2012; 13(6):607-615.[PubMed Abstract]

- Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2013; 105(3):175-201.[PubMed Abstract]

- Collins S, Mazloomzadeh S, Winter H, et al. High incidence of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women during their first sexual relationship. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2002; 109(1):96-98.[PubMed Abstract]

- Winer RL, Feng Q, Hughes JP, et al. Risk of female human papillomavirus acquisition associated with first male sex partner. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2008; 197(2):279-282.[PubMed Abstract]

- Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Wacholder S, et al. Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: A randomized trial. JAMA 2007; 298(7):743–753.[PubMed Abstract]

- Schiller JT, Castellsague X, Garland SM. A review of clinical trials of human papillomavirus prophylactic vaccines. Vaccine 2012; 30 Suppl 5:F123-138.[PubMed Abstract]

- Mirghani H, Amen F, Blanchard P, et al. Treatment de-escalation in HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma: Ongoing trials, critical issues and perspectives. International Journal of Cancer2015;136(7):1494-503[PubMed Abstract]

- Urban D, Corry J, Rischin D. What is the best treatment for patients with human papillomavirus-positive and -negative oropharyngeal cancer? Cancer 2014; 120(10):1462-1470.[PubMed Abstract]

- Shi R, Devarakonda S, Liu L, Taylor H, Mills G. Factors associated with genital human papillomavirus infection among adult females in the United States, NHANES 2007-2010. Biomed Central Research Notes2014; 7:544.[PubMed Abstract]

- McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncology 2008; 9(5):425-434.[PubMed Abstract]